Eli Stowers stood on a Denton-area football field three summers ago after a workout that his father organized to lift his spirits. Stowers, a quarterback at Texas A&M, had not yet fully accepted the fact that he could no longer physically play the position that had him on a professional path.

“I don’t know what to do,” Stowers told his father. “I don’t want to go back. I can’t play this position anymore.”

Donald Stowers, a former high school football coach, glanced at the stopwatch he had just used to hand time his son’s 40-yard dash effort.

“You’re 6-4, 220 pounds and you run a 4.39,” his father said. “You can play any position you want.”

That, Donald Stowers will remind any and all who ask him, is how he’d always intended to raise his hyper-athletic child whose professional goals were supported early by gifted feats.

The family still couldn’t have imagined this.

Stowers, once a standout quarterback at Denton Guyer who expected to be the next-great signal caller at A&M, is now considered among the nation’s best tight ends for a Vanderbilt team that’s shaken it’s long-held bottom-feeder reputation.

He’s the third-ranked tight end on ESPN’s NFL draft big board. Pro Football Focus ranks him fifth. His 31 catches and 397 yards both lead the ninth-ranked Commodores (7-1, 3-1 SEC) who will play No. 20 Texas at DKR-Texas Memorial Stadium this Saturday in a game that could decide the postseason fate of each program.

It only took a crumbled dream, next-level abilities and a definitive transition.

“The normal young man does not survive that,” former Guyer coach John Walsh said, “but the way he walks in his faith is what got him through it.”

Survival may be an understatement.

“God works in mysterious ways,” Stowers told The Dallas Morning News Thursday afternoon. “Sometimes it doesn’t make sense. My life didn’t make sense.”

Related

Otherworldly athleticism

There’s a hill in Denton’s Oakmont neighborhood near the family’s home that Stowers figures is roughly 150 meters long from top to bottom. The father-son duo, often multiple times a week when Stowers was a high schooler, would use it as a mechanism to train speed.

Former Guyer offensive coordinator Lee Vallejo — who now works with Walsh at San Marcos — once witnessed Stowers run down the hill at full speed under his father’s direction.

“I was driving down one day,” Vallejo said. “I said, ‘holy s—, that’s Eli and Don.’ What’re we doing here guys?”

Stowers laughed Thursday at the memory. Uphill runs, he said, build muscle. Downhill runs, or “overspeed training,” are designed to improve coordination and reaction time.

“We found a way to get better,” Stowers said.

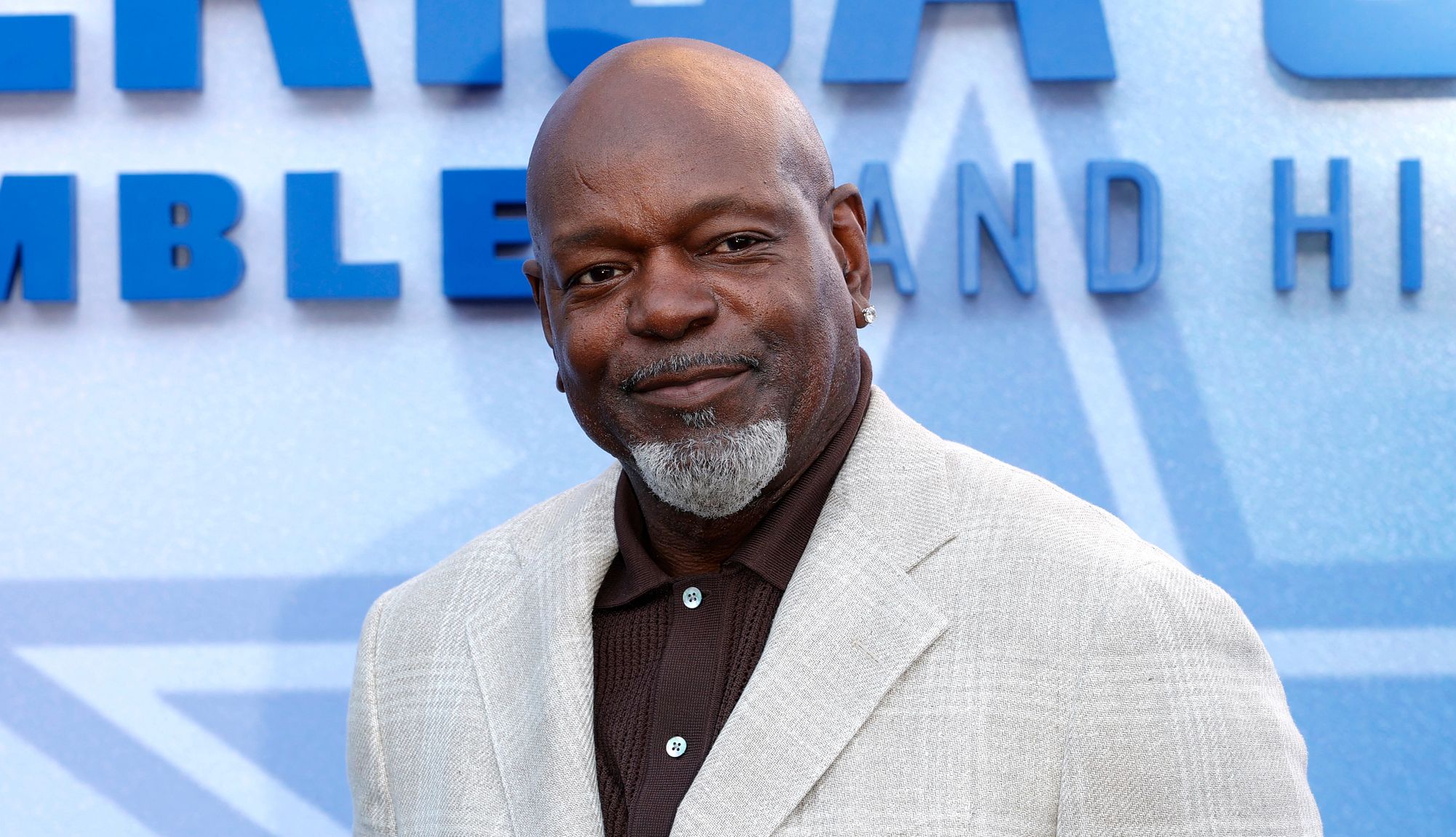

Donald Stowers played defensive back at New Mexico State and coached high school football in Texas for multiple decades before he joined the corporate workforce when his son reached middle school. Stowers was introduced to football as a 4-year-old and was taught schematics in elementary school.

Eli Stowers (left) with his father Donald Stowers (right). Donald is a former high school football coach who coached his son Eli in little league football.

Courtesy / Donald Stowers

One day, when his father was the head coach at Little Elm, Stowers walked into his office and was given a marker, a whiteboard and instructed to draw a Cover 2 defense.

“I’m literally like 6 years old,” Stowers said. “A lot of times you don’t learn this stuff until you’re dang near in college. It just made it so much easier.”

Otherworldly athleticism helps, too. Stowers, now 6-4, 235 pounds, has been named to The Athletic’s freak list — an honor roll that charts college football’s best athletes — for two consecutive seasons. His reported 39-inch vertical leap and 21.43 mph top-end speed were big sellers.

“I’ve always trained my kids to be an athlete first,” Donald Stowers said. “Just go be the best athlete. You kind of figure out what you want to do sports-wise depending on what your love is. The good thing about being an athlete? If a sport doesn’t work out, you go play a different sport. Or if it doesn’t work out at a certain position, you go play a different position.”

Stowers played quarterback in little league because “he was the best athlete,” but when his father coached his 7-on-7 team, he made sure that there was a healthy dose of defense and skill position reps, too. Stowers outjumped eventual Los Angeles Chargers wide receiver Quentin Johnston at the 2019 Texas Relays and won the 6A state championship months later with a 7-foot leap in the high jump. He first dunked in a basketball game as a middle schooler and was the sixth man on a nationally ranked Guyer team during his freshman season.

He earned scholarship offers from Baylor, Oregon and TCU before he ever started a varsity football game. The Aggies offered him before his junior season, and he committed five months later.

Stowers knew he could play elsewhere if necessary, and Walsh believed he could’ve been an NFL-caliber safety with his size and speed. Vallejo had a play-call tucked away that would’ve used Stowers as a Hail Mary jump-ball threat if Guyer required any last-minute magic because “he’ll go catch the sucker.”

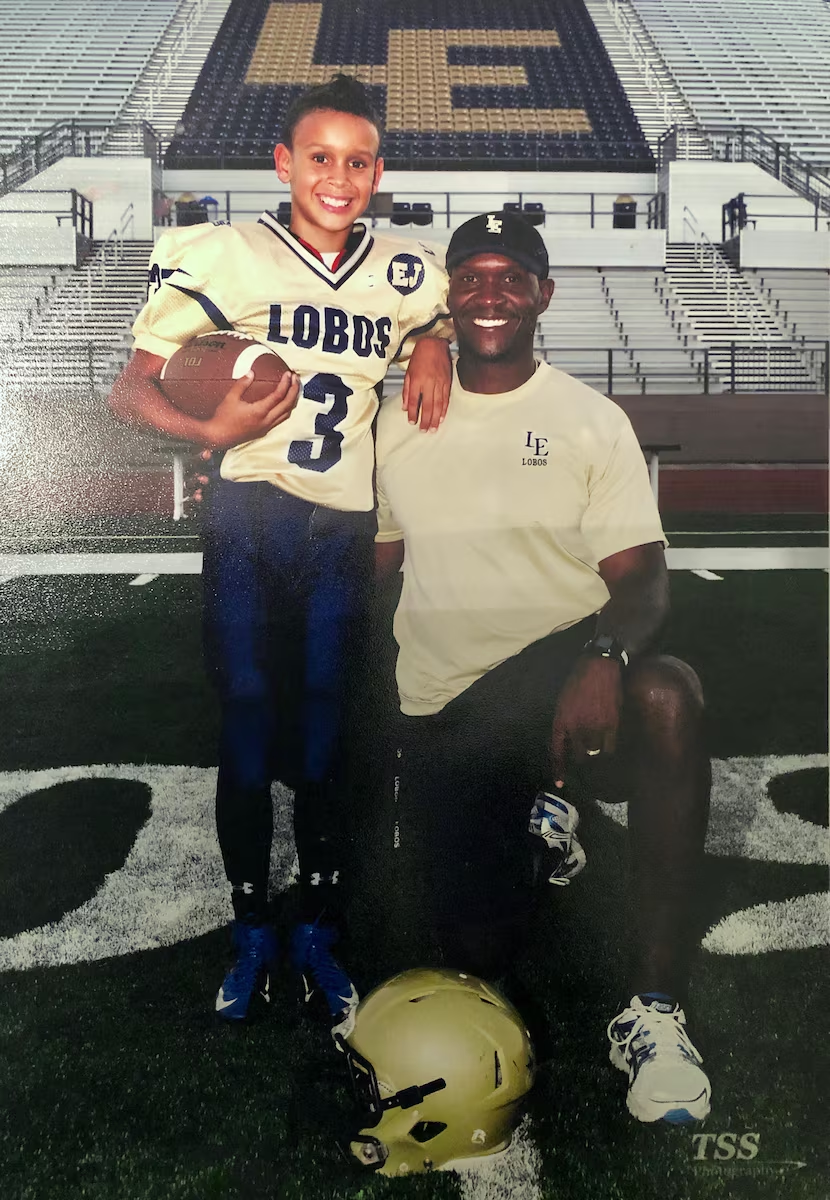

Denton Guyer High School quarterback Eli Stowers (3) throws a pass during the first half as Denton Guyer High School played Cedar Hill High School in the Class 6A Division II, state semifinal at McKinney ISD Stadium in McKinney on Saturday, January 9, 2021. (Stewart F. House/Special Contributor)

Stewart F. House / Special Contributor

Rockwall-Heath coach Rodney Webb — who coached Guyer from 2021-23 — thought he could have shined at wide receiver in his senior season but didn’t dare move him after his success at quarterback in the two years prior.

Understandably so. Stowers was a four-star recruit and the 12th-ranked high school quarterback in a class that included future professionals Quinn Ewers, Caleb Williams, Drake Maye, J.J. McCarthy, Jaxson Dart, Jalen Milroe and Shedeur Sanders. He passed for 6,945 yards, rushed for 3,323 and totaled 105 touchdowns in three seasons as Guyer’s starter.

“I was going to the NFL as a quarterback,” Stowers said. “That was my dream growing up. That’s all I knew.”

That’s what made everything that followed as difficult as it was.

Losing the ability to throw

Stowers could no longer throw a football when he arrived on Texas A&M’s campus.

His father first thought that it might’ve been the yips. Walsh believes that the intensive rehab he underwent after he tore his PCL and meniscus in the 6A Div. II state championship game as a junior might’ve interfered with his mechanics. A shoulder injury — which dated to high school and later developed into a torn labrum — could’ve ultimately been the cause.

Denton Guyer’s quarterback Eli Stowers (5) is led off the field after getting injured in in the first quarter of a Class 6A Division II state championship game against Austin Westlake at the AT&T Stadium in Arlington, on Saturday, December 21, 2019. Westlake leads at halftime 14-0. (Juan Figueroa/The Dallas Morning News)

Juan Figueroa / Staff photographer

“That was one of the toughest parts of my life because I didn’t even know what was going on,” Stowers said. “All of a sudden I just can’t do it anymore. It almost, in a way, hurt my pride.”

“He was in a dark place,” Donald Stowers said. “He was just depressed. I had to go up a couple days just to see Eli, hang out, be a dad. It broke my heart when I left. I could just see it in his eyes.”

The “how” and “why” took a backseat to the “what now” as Stowers joined a quarterback room that included Zach Calzada and Haynes King. Then-A&M coach Jimbo Fisher temporarily moved Stowers to tight end to fill a positional need but kept the door open for a return to quarterback. But Stowers, even after consultation with numerous trainers, still couldn’t throw the football more than 10 yards down the field.

Stowers underwent surgery on his torn labrum after his freshman season and returned to quarterback full time in his sophomore year. Fisher, though, informed the family that the team planned to transition Stowers into a full-time wide receiver/tight end role before his junior season. That, coupled with what Donald Stowers described as “culture” issues within the program, triggered a trip to the transfer portal.

The switch

Surely, Stowers believed, he’d beat out a two-star junior college product for New Mexico State’s quarterback gig. Instead Diego Pavia — a New Mexico Military Institute transfer who’s now a Heisman Trophy contender at Vanderbilt — held a clear advantage in spring ball.

Stowers recognized the reality of his situation, conceded his longtime dreams and informed head coach Jerry Kill that he’d play any position — on defense or offense — in order to see the field. He transitioned to tight end full-time prior to his junior season, joined the same church in Las Cruces, N.M., that his father attended decades prior and viewed the change as a message from God that had long awaited a response.

“I felt so much peace,” Stowers said. “I just think I didn’t want to listen for a while.”

The position’s bare bones weren’t hard for Stowers to understand. He bulked up to 230 pounds, retained his speed and athleticism and operated under a directive to “go be a good athlete and get open.” He credits his hands to thousands of snaps taken at quarterback and his father’s frequent and impromptu passes thrown over the years.

New Mexico State quarterback Eli Stowers runs for yardage during an NCAA football game against UTEP on Wednesday, Oct. 18, 2023, in El Paso, Texas.

Andres Leighton / AP

He caught 36 passes for 366 yards and two touchdowns in his debut season at tight end before he followed Kill, Pavia and offensive coordinator Tim Beck to Vanderbilt prior to the 2023 season. Stowers received a “pretty significant” name, image and likeness deal from the Commodores, his father said, and was the unquestioned starter at his position for the first time since high school.

Stowers caught 19 passes and one touchdown in Vanderbilt’s first four games last season. He had six catches for 113 yards in a 40-35 win vs. No. 1 Alabama on Oct. 5 that announced to the college football world that Vanderbilt was no longer a pushover and that Stowers was more than just a positional castoff.

Walsh was at his daughter’s volleyball match when he learned what his former quarterback did against a certified blue blood program.

“I heard he was the leading receiver,” Walsh said. “And I was like, ‘Alright, this is coming to fruition.’ After that, all I did was get my popcorn ready. I had to find the Vandy games the rest of the year and just enjoy it.”

Stowers finished the season with 49 catches, 638 yards, six touchdowns and was named first-team All-SEC at the tight end position and a semifinalist for the Mackey Award. He opted out of the 2025 NFL draft to further improve at the relatively new position and continue what he and Pavia started at Vanderbilt.

Saturday, in Austin, a seismic opportunity awaits to do that. The Commodores can further certify their status as legitimate College Football Playoff contenders against a program that reached the national semifinals in each of the previous two seasons. Stowers — who’ll play in his home state for the first time in over two years — will attempt to do what’s long been the goal since he first joined the program in College Station four years ago.

Beat the Longhorns.

Certify NFL dreams.

“It’s a blessing,” Stowers said. “It really is.”

Find more college sports coverage from The Dallas Morning News here.